Nikolai Konstantinovich Koltsov (July 3 (15), 1872, Moscow - December 2, 1940, Leningrad) - an outstanding Russian biologist, author of the idea of matrix synthesis.

N.K. Koltsov is rightly called the founder of Russian experimental biology. He was the first to develop a hypothesis of the molecular structure and matrix reproduction of chromosomes, which anticipated the fundamental principles of modern genetics. In science, he went from comparative anatomy of vertebrates to experimental cytology. And he moved further - to physical and chemical biology, through the magnifying glass of which you can see not only cells, but also individual molecules. And even their parts are genes.

Koltsov was a “merchant’s son”, born in Moscow into the family of an accountant for a large fur company. He brilliantly graduated from the Moscow Gymnasium. In 1890 he entered the natural sciences department of the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics of Moscow University, where he specialized in the field of comparative anatomy and comparative embryology. Koltsov’s scientific supervisor during this period was the head of the school of Russian zoologists M.A. Menzbier.

In 1890, N.K. Koltsov entered Moscow University, from which he graduated in 1894 with a first-degree diploma and a gold medal for his essay “The Belt of the Hind Limbs of Vertebrates.”

N.K. Koltsov specialized under the guidance of the early deceased private associate professor, later professor of embryology and histology V.N. Lvov. As Nikolai Konstantinovich recalled, it was Lvov who gave him the work of A. Weisman “On the Rudimentary Path” to read, which had a great influence on the formation of the young scientist. The works of Lamarck, Darwin, Gegenbauer, Schopenhauer, Kant, and Spinoza appear on N.K. Koltsov’s desk. N.K. Koltsov knows German, English and French well, and later Italian was added to them.

N.K. Koltsov completed his diploma work under the guidance of Professor Menzbier. This thesis is still kept in the library of the Institute of Developmental Biology of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

In 1895, Menzbier recommended that Koltsov leave the university “to prepare for a professorship.” Since 1899, Koltsov has been a private assistant professor at Moscow University. After three years of studies and successfully passing six master's exams, Koltsov was sent abroad for two years. He worked in laboratories in Germany and at marine biological stations in Italy. The collected material served as the basis for a master's thesis, which Koltsov defended in 1901. Koltsov’s works on the biophysics of the cell and, especially, on the factors that determine the shape of the cell, have become classic and are included in textbooks.

Even during his studies, Koltsov’s interests began to turn from comparative anatomy to cytology. Having received the right to a privatdocent course after returning from a business trip abroad, he begins to lecture precisely on this subject. In 1902, Koltsov was again sent abroad, where for two years he worked in the largest biological laboratories and at marine stations. These years coincided with a period when in biology there was a decline in interest in purely descriptive morphological sciences and new trends began to emerge - experimental cytology, biological chemistry, developmental mechanics, genetics, which opened up completely new approaches to understanding the organic world. During his second trip abroad, N.K. Koltsov completed the first part of his classic research on cell shape - a study on the sperm of decapods with general considerations regarding the organization of the cell (1905), intended for a doctoral organization. This work, together with the second part of research on cell shape, has become established in science as the “ring principle” of shape-determining cell skeletons (cytoskeletons).

Returning to Russia in 1903, N.K. Koltsov, without stopping scientific research, began intensive pedagogical and scientific-organizational work. The course of cytology, which began in 1899, grew into a hitherto unknown course of general biology. The second course taught by Koltsov, “Systematic Zoology,” was very popular among students. The “Big Zoological Workshop” created by N.K. Koltsov, where students were accepted by competition, formed a single whole with the lectures.

In 1905, the time of the first Russian revolution, a young private assistant professor entered the circle of “eleven hot heads.” His social activities bring him into conflict with the leadership of the department, as a result of which he himself cancels the defense of his already prepared doctoral dissertation. Subsequently, N.K. Koltsov recalled: “I refused to defend my dissertation on such days behind closed doors: the students were on strike, and I decided that I did not need a doctorate. Later, with my speeches during the revolutionary months, I completely upset my relationship with the official professorship, and the thought of defending my dissertation no longer occurred to me.”

At the beginning of 1906-1907. N.K. Koltsov was asked to vacate the office he occupied, and in the spring of 1907 the work room was also taken away. N.K. Koltsov converted his personal apartment into a laboratory. In 1909-10 N.K. Koltsov was suspended from teaching classes at the Institute of Comparative Zoology. N.K. Koltsov was left with only a course of lectures on invertebrate zoology. In 1903, he began teaching as a professor at the Higher Women's Courses, where he worked until 1924.

Beginning his work during the heyday of descriptive biology and the first steps of experimental biology, Koltsov had a keen sense of the trends in the development of biology and early realized the importance of the experimental method. This was not a simple biological experiment, but the use of methods of physics and chemistry. Koltsov more than once emphasized the enormous importance for biologists of the discovery of new forms of radiant energy, in particular, X-rays and cosmic rays, and wrote about the use of radioactive substances. The discovery of X-ray diffraction on crystals prompted Nikolai Konstantinovich to make this prophetic statement: “Biologists are waiting for these methods (X-ray diffraction analysis) to be improved so much that it will be possible to use them to study the crystal structure of intracellular skeletal solid structures of protein and other nature.” And so it happened. It was the X-ray diffraction method that helped scientists decipher the secret of the DNA molecule.

Koltsov’s other prediction, the “chemical” one, also came true. He believed that every complex biological molecule arises from a similar pre-existing molecule. Therefore, chemists, in his opinion, should follow the path of creating new molecules in solutions containing the necessary components of complex molecules by introducing into them seeds of ready-made molecules of the same structure.

In 1916, N.K. Koltsov tried to find the causes of mutations. The scientist considered radioactive radiation and active chemical compounds to be catalysts for mutations. However, revolutions and wars did not allow N.K. Koltsov and his collaborators to experimentally prove their hypothesis. In 1925, G. Nadson and G. Fillipov managed to do this, however, the Nobel Prize for this discovery went to the American biologist G. Miller.

In 1916, N.K. Koltsov became a corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. In 1917, the Institute of Experimental Biology was created, headed by N.K. Koltsov. Until the end of the thirties, the institute was at the forefront of biological science. Within its walls, new areas of knowledge are opening up, and bridges are being built between them. Here N.K. Koltsov had the opportunity to combine a number of the latest trends in modern experimental biology in order to study certain problems from different points of view and, if possible, using different methods. We talked about developmental physiology, genetics, biochemistry and cytology.

Genetics was one of N.K. Koltsov’s favorite disciplines. Back in 1921, he published an experimental work “Genetic analysis of color in guinea pigs.” Nikolai Konstantinovich did not ignore the famous martyr of science, the Drosophila fly. He tried to establish connections between genetics and evolutionary teaching. Under his patronage, the Anikov genetic station was organized, the task of which was to introduce scientific achievements into animal husbandry practice. In 1920, this station united other, smaller ones, resulting in the Central Station for the Genetics of Farm Animals. For many years, the station was led first by N.K. Koltsov himself, and then by his students.

In 1920, with the active participation of Koltsov, the Russian Eugenics Society arose, at the same time a eugenics department was organized at the Institute of Experimental Biology, which launched research on human medical genetics, as well as on such issues of anthropogenetics as the inheritance of hair and eye color, variability and heredity of complex traits in identical twins, etc. The department had its first medical genetic consultation.

In 1920, Koltsov was considered as one of the defendants in the Tactical Center case.

And he was sentenced by the Supreme Revolutionary Tribunal, among nineteen accused, to death, but the execution was replaced, according to some sources, by a suspended prison sentence of five years, according to others - to a concentration camp until the end of the civil war.

In 1930, the All-Union Institute of Animal Husbandry opened, which included the Central Genetic Station, becoming the genetics sector. N.K. Koltsov was appointed head of this sector. In 1935, N.K. Koltsov was elected academician of the All-Russian Academy of Agricultural Sciences and Doctor of Zoology.

N.K. Koltsov raised a galaxy of wonderful students, including N.V. Timofeev-Resovsky, S.S. Chetverikov, B.L. Astaurov, V.V. Sakharov, I.A. Rapoport, N.P. Dubinin, V.P. Efroimson.

In the second half of the thirties, Soviet biology suffered a crushing blow. The most advanced areas of life science were especially affected: cytology, molecular biology, genetics. N.K. Koltsov also felt the blow of the cold wind of dogmatism. In 1938, he was forced to resign as director of the Institute of Experimental Biology, to which he devoted more than twenty years of his life. In 1976, the Institute of Developmental Biology of the USSR Academy of Sciences was named after N.K. Koltsov.

N.K. Koltsov was a full member of the Moscow Society of Natural Scientists for many years, made presentations at its meetings, and published in the proceedings of the Moscow Society of Naturalists.

In the fall of 1940, Koltsov went to Leningrad. He suffered a heart attack at the Evropeiskaya Hotel. At that moment he was writing the text of the speech “Chemistry and Morphology” for the anniversary meeting of the Moscow Society of Natural Scientists. On December 2 he died.

Scientific achievements:

He showed, mainly on the sperm of decapod crustaceans, the formative significance of cellular “skeletons” (Koltsov’s principle), the effect of ionic series on the reactions of contractile and pigment cells, and physicochemical effects on the activation of unfertilized eggs for development. He was the first to develop the hypothesis of the molecular structure and matrix reproduction of chromosomes (“hereditary molecules”), which anticipated the most important fundamental principles of modern molecular biology and genetics (1928).

On July 15, 1872, Nikolai Koltsov, an outstanding biologist, geneticist, and founder of Russian experimental biology, was born.

Private bussiness

Nikolai Konstantinovich Koltsov (1872-1940) born in Moscow, in the family of an accountant for a large fur company. At the age of eight he entered the Sixth Moscow Gymnasium, from which he graduated with a gold medal. He was fond of collecting plants and insects, and walked around the entire Moscow province, and later the entire Crimea. In 1890, N.K. Koltsov entered Moscow University, from which he graduated with a first-degree diploma and a gold medal for his essay “The Belt of the Hind Limbs of Vertebrates.” He was left at the department “to prepare for a professorship.” In 1897-1898 he went on an internship in Europe, where he worked in laboratories and biological stations in Denmark, Italy, France and Germany. I visited the Mediterranean biological station in Villafranca, where scientists from Russia were working at that time. Based on the research materials of these years, I prepared my master’s thesis “Development of lamprey. On the issue of metamerism of the head of vertebrates".

During these years there was a transition of Koltsov's scientific interests from comparative anatomy to cytology and the newly emerging biochemistry and genetics. He came to the conclusion that it was necessary to focus research not on fixed, but on living cells with which experiments could be carried out. The result of his work was the monograph “Research on the Shape of Cells,” where he came to the conclusion that this shape is determined by intracellular skeletal structures, and the movement of the cell is determined by the interaction of the liquid contents with these structures. This is how the modern doctrine of the cytoskeleton was born.

In 1909, for participation in political activities, Koltsov was suspended from classes, and in 1911, together with other leading teachers of Moscow University, he resigned and taught at the Higher Women's Courses and at the Moscow People's University Shanyavsky. At the People's University he created a laboratory of experimental biology. In 1916 he was elected a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences.

In the summer of 1917, Nikolai Koltsov headed the Institute of Experimental Biology in Moscow. Initially it was an independent institution with only four full-time employees, including the director, but many of Koltsov's students worked there on a voluntary basis. In 1920, by order of the People's Commissar of Health N.A. Semashko, the institute was included in the system of scientific institutions of the People's Commissar of Health of the RSFSR, and it quickly turned into a large scientific center.

In 1920, he was arrested in the so-called “Tactical Center” case and sentenced to death, commuted to a suspended prison sentence. Released by personal order of Lenin.

During his years of work at the Institute of Experimental Biology, Koltsov expressed a number of fruitful ideas, which were developed by his students. In particular, he, ahead of his foreign colleagues, put forward hypotheses about chemical and radiation mutagenesis. In 1935, N.K. Koltsov became an academician of the All-Russian Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

At the end of the 1930s, when the struggle against “bourgeois genetics” began in Soviet biology, N. Koltsov was among the consistent opponents of T. Lysenko and his supporters. In 1939, he was removed from his post as director of the Institute of Experimental Biology.

On December 2, 1940, Nikolai Koltsov was in Leningrad, in a hotel, where he was working on a report on the topic “Chemistry and Morphology.” On this day he had a massive heart attack, from which the scientist died. He was buried in Moscow along with his wife, Maria Sadovnikova-Koltsova, who took poison after his death.

What is he famous for?

Nikolay Koltsov

The creation of the Institute of Experimental Biology by N.K. Koltsov had a decisive influence on the development of domestic biological science. Koltsov’s goal was “to unite in one research institution a number of the latest trends in modern experimental biology in order to study certain problems from different points of view and, if possible, using different methods.” The Institute became an authoritative scientific center, where, through Koltsov’s efforts, a strong school of experimental biologists, primarily cytologists and geneticists, was developed. After a number of transformations and administrative changes, this institute is now called the N.K. Koltsov Institute of Developmental Biology of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

What you need to know

In 1927, in the report “Physico-chemical foundations of morphology” of the idea of matrix synthesis of “hereditary molecules” at the Third All-Russian Congress of Zoologists, Anatomists and Histologists in Leningrad, Koltsov put forward the idea of “matrix synthesis” of hereditary molecules, which is now known as replication - the process of synthesis of a daughter molecule on the parent matrix. His mistake was only that, according to his assumption, the carriers of hereditary characteristics in the chromosome were large protein molecules, and the “letters” were the individual amino acids of these proteins. Only 26 years later, J. Watson and F. Crick discovered that DNA and nucleotides play this role, but DNA doubling occurs precisely according to the principle formulated by N.K. Kolv.

Direct speech

“Students were allowed to participate in a large workshop after an interview with Koltsov, and a mandatory condition for admission was knowledge of at least one of the European languages. To students who did not speak any language, Koltsov said: “Learn the language and come back in a year.” It was allowed to use books and articles during exams. Each trainee received a workplace, a microscope, the necessary materials and could work at any time of the day and for as long as they wanted. The latter was of great importance, since some students had to earn a living in their free time. Once a week, Koltsov, and later his deputies, gave each student an assignment and brought literature (in the first years it was only in foreign languages). Students studied living objects, performed experiments, used cytological, physicochemical and other methods, and mastered microscopic techniques. Koltsov periodically talked with each student about the results of his work.” From the memoirs of T. A. Detlaf

“...During a discussion on genetics and selection in December 1936, Nikolai Konstantinovich behaved irreconcilably towards those who attacked genetics (primarily Lysenko’s supporters). Understanding, perhaps better and more clearly than all his colleagues, what the organizers of the discussion were driving at, after the session closed, in January 1937 he sent a letter to the President of the All-Russian Academy of Agricultural Sciences, in which he directly and honestly stated that organizing SUCH a discussion is patronizing liars and demagogues , will not bring any benefit to either science or the country. He focused on the unacceptable situation with the teaching of genetics in universities, especially in agronomic and livestock... Koltsov began to be subjected to harsh public attacks in the spring of 1937. An example was set by the head of the agricultural department of the Central Committee of the party, Ya.A. Yakovlev, who qualified Koltsov as a “fascist obscurantist.. ... trying to turn genetics into a weapon of reactionary political struggle." Soifer V.N. Power and science. The history of the defeat of genetics in the USSR.

5 facts about Nikolai Koltsov

- During the 1905 revolution, Koltsov was a member of a circle led by Pyotr Sternberg. For some time, work was going on in Koltsov’s office to reproduce leaflets. After the December armed uprising in Moscow, Koltsov wrote the book “In Memory of the Fallen. Victims from among Moscow students in October and December days,” which was confiscated on the day of its release.

- For a long time, N.K. Koltsov was an enthusiast of eugenics. He founded the Russian Eugenics Journal and headed the Russian Eugenics Society. After the condemnation of eugenics in the USSR, Koltsov was repeatedly reminded of this activity by his opponents in discussions about genetics at the All-Russian Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

- Founded in 1919 by Koltsov at the Faculty of Biology of Moscow University, the Department of Experimental Biology gave rise to five departments: genetics, physiology, developmental dynamics, hydrobiology and histology.

- Koltsov was one of the founders of the Zvenigorod Biological Station, where 1st and 2nd year students of the Faculty of Biology of Moscow State University still do their internship every year.

- Among Koltsov’s students are famous biologists N.V. Timofeev-Resovsky, S.S. Chetverikov, B.L. Astaurov, V.V. Sakharov, I.A. Rapoport, N.P. Dubinin, V.P. Efroimson.

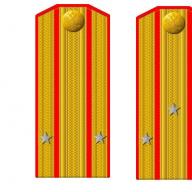

ROLTS Nikolai Konstantinovich (15.7.1872, Moscow - 2.12.1940, Leningrad) - biologist; founder of Russian experimental biology; Doctor of Zoology (1935); Corresponding member Petersburg Academy of Sciences (1916), Russian Academy of Sciences (1917), Academy of Sciences of the USSR (1925), acad. VASKHNIL (1935); organizer and first director. Institute of Experimental Biology (1917–39).

In 1890 he entered the natural sciences department of physics and mathematics. Faculty of the Imperial Moscow University (IMU), specialized in the region. comparative anatomy and comparative embryology. K.'s supervisor was the head of the Moscow zoological school M.A. Menzbier. In 1894 he took part in the IX Congress of Russian naturalists and doctors, where he made a report “The importance of cartilaginous centers in the development of the vertebrate pelvis.” He carried out fundamental research “The hind limb girdle and hind limbs of vertebrates”, for which K. was awarded a gold medal. After graduating from university (1894) he was left at the department. to prepare for prof. title and after passing the master's exams, he was sent abroad for two years. He worked in laboratories in Germany and at marine biological stations in Italy. The collected material served as the basis for a master's thesis. on the metamerism of the head of vertebrates (1901), which was immediately recognized as a classic. In diss. outlined the outlines of a completely different direction in biology - a physical and chemical explanation of the form of living formations. In 1902 he again went abroad, where he became acquainted with new achievements in biology - experimental cytology, biological chemistry, mechanics of development, and genetics. Communication with the largest European cytologists: W. Fleming, O. Büchli, R. Goldschmidt, M. Hartmann - determined the change in scientific research. interests of K. During his second trip abroad, he completed the first part of his classic “Research on the shape of the cell” - “A study on the sperm of decapods in connection with general considerations regarding the organization of the cell” (1905), intended for Dr. diss. This work, together with the second part of “Studies on the Shape of the Cell” (1908), became established in science as the “Ring Principle” of shape-determining cell skeletons (cytoskeletons). Returned to Russia in 1903. Without stopping his scientific work. research, engaged in intensive pedagogical and scientific-organizational work. The course of cytology, which began back in 1899, was transformed into a completely new course of general biology. K.’s other course, “Systematic Zoology,” was also extremely popular among students. The “Big Zoological Workshop” formed a single whole with the lectures, where students were accepted by competition. In the beginning. 1906 K. refused to defend Dr. diss., supporting t.o. the outbreak of a student strike. He consistently advocated for university freedoms and helped print manifestos of the student committee. In 1909, for participation in political activities, he was suspended from classes at the IMU, and in 1911, together with other leading profs. and Assoc. resigned. He taught at the MVZhK and at the Moscow City People's University named after. A.L. Shanyavsky. He worked at the MVZhK and the 2nd Moscow State University from 1903–24. Together with F.N. Krasheninnikov, L.M. Krechetovich and M.A. Menzbier participated in the development of textbooks. programs in biology for MVZhK. Scientific research was also formed here. school K. Put forward the idea of creating the Institute of Experimental Biology (IEB). In September 1916, dir. new institute (opened in the summer of 1917). He shared the views of the People's Socialists; during Denikin's attack on Moscow in August 1919, K. took part in the discussion of issues of restoring the socio-economic life of Russia. Later he was convicted in the “Tactical Center” case (1920), but the sentence (execution) against K. was overturned personally by V.I. Lenin thanks to the petitions of P.A. Kropotkin, M. Gorky, A.V. Lunacharsky. Opposed the official position on genetics, which was formulated by Lysenko and Present; the result of this was devastating articles in the press against K. To the article “Pseudo-scientists have no place in the Academy of Sciences,” I responded with a personal letter to I.V. Stalin. In the 1920s, headed by K., the Russian Eugenics Society was created, and N.A. took part in its work. Semashko, A.V. Lunacharsky, G.I. Rossolimo, D.D. Pletnev, S.N. Davidenkov, A.I. Abrikosov. Having a broad understanding of eugenics, he included in it the compilation of genealogies, the geography of diseases, vital statistics, social hygiene, etc. The core of K.'s eugenics was research into the genetics of human mental characteristics, types of inheritance of eye and hair color, biochemical indicators and blood groups, the role of heredity in the development of a number of people. diseases, examination of monozygotic twins. After K.'s death, his ideas, especially in the field of eugenics, were constantly criticized, and only now many of them are recognized by science. He continued to analyze the shape of molecules and the physical and chemical explanation of the forms of living formations. He believed that a chromosome is a molecule or a bundle of molecules with a linear arrangement of genes on them. On this basis, K. substantiated the crossing-over mechanism (1903). He formulated the matrix principle of reproducing “hereditary molecules”, on which later ideas about the “double helix” are based. Turning to the development of form from the egg to the organism, he studied individual development in terms of a force field. Treating genes as modifiers of the single force field of the organism, he clarified the actual role of those embryonic rudiments, which were usually considered useless, and showed how the entire species in its past and present, and to some extent the entire biosphere, worked on each nascent organism.

Elected honor. member Edinburgh Royal Society (1933), awarded the title of Honored Scientist of the RSFSR (1934).

Students: V.V. Sakharov, N.V. Timofeev-Resovsky, B.L. Astaurov and others.

Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences V. SOIFER

We sing a song to the madness of the brave.

A. M. Gorky

There are many tragic pages in the history of Russian science. A difficult fate befell the most talented Russian scientists, who had to work at a time when science was under the yoke of politics and ideology. Biology, and especially genetics, suffered the most. The journal "Science and Life" has addressed this topic more than once; on its pages were published materials dedicated to N. I. Vavilov, N. V. Timofeev-Resovsky and other scientists, whose scientific and personal fate was in one way or another crippled by government intervention. In this issue we publish another tragic story; its hero is the outstanding biologist Nikolai Konstantinovich Koltsov, many of whose discoveries were ahead of their time and remained undeservedly forgotten. We present to our readers a journal version of a chapter from the new revised and expanded edition of the book “Power and Science. The History of the Communists’ Destruction of Genetics in the USSR.” Its author, Professor V.N. Soifer, is not only a well-known specialist in the field of molecular biology, but also a historian of science, who has published several books, including “Essays on the History of Molecular Genetics” and “Red Biology.” (Read the interview with V.N. Soifer in the magazine "Science and Life" No. 3, 2002)

CHARACTER FORMATION AND YEARS OF STUDY

N.K. Koltsov on vacation in the south. 1939 (?). (The photograph was taken by Koltsov’s student V.V. Sakharov and presented to the author in 1955.)

N.K. Koltsov with a group of scientists at the Russian Zoological Station in Ville-Franche.

Koltsov is a high school student. From the book: V. Polynin. A prophet in his own country. - M.: Soviet Russia, 1969.

Intracellular cytoskeletal fibers. The term “cytoskeleton,” proposed by Koltsov at the beginning of the twentieth century, was forgotten and reintroduced only in the late 1970s.

Drawing by N.K. Koltsov (1927), illustrating his hypothesis of the structure of hereditary molecules, according to which each chromosome of somatic cells contains two double molecules of hereditary material (each molecule carries two identical copies).

N. A. Alekseev (1852-1893).

S. S. Chetverikov (1880-1959).

K. S. Stanislavsky (1863-1938).

Russian Science Week in Berlin. 1927

Maria Polievktovna Sadovnikova-Koltsova. From the book: V. Polynin. A prophet in his own country. - M.: Soviet Russia, 1969.

Nikolai Koltsov was born on July 3, 1872 in Moscow into a merchant family. His father died when Kolya was not even a year old, so the children grew up and were raised under the guidance of their mother, who also came from a merchant family. Nikolai Koltsov’s older brother, Sergei, wrote in his memoirs about the family:

“Our mother was an educated woman. She knew French and German, loved to read, thanks to which we always had a lot of books, there were always so-called thick magazines - “Bulletin of Europe”, “Notes of the Fatherland”, “Russian Thought” and others.”

Kolya Koltsov began to show interest in all living things early. As his older brother recalled, “he was no more than six years old when they gave him a [toy] horse, and the first thing he did with it was to cut open its belly, wanting to see what was in it. His mother, seeing this, said: “Well, you should be a natural scientist." After graduating from the 6th Moscow Gymnasium with a gold medal, he entered the Moscow Imperial University. In 1894, Koltsov’s thesis “The Belt of the Hind Limbs of Vertebrates,” completed under the guidance of the outstanding zoologist Professor M. A. Menzbier, was awarded a gold medal (it was a book written in calligraphic handwriting and containing many original drawings in the format of an encyclopedia and volume of about 700 pages), and he himself was left in graduate school (“in preparation for the professorship,” as they said then).After passing in 1896, all Due to the exams required for graduate students, he was sent in 1897, at the expense of the university, to undergo an internship in the best laboratories in Europe.

First, Koltsov went to the University of Kiel (Germany) to work with Walter Flemming (1843-1905), the recognized founder of a new direction - cytogenetics. In 1879, Flemming was the first to describe the behavior of chromosomes during cell division (it was he who called the process mitosis). The term "chromosome" had not yet been coined, and Flemming described "the cell division behavior of long, thin structures stained by the newly discovered dye, aniline." From Kiel Koltsov moved to Naples, to the zoological station, and then went to France - to Roscov and Ville-Franche. Particularly useful was the work in Ville-Franche, where the Russian Zoological Station had existed since 1884. Scientists from all countries came there, including from overseas, and it was quite natural that Koltsov became friends with young scientists who later became world-recognized leaders of biology, such as the American Edmund Wilson (a few years later he invited work of Thomas Morgan, who, with three students, developed the chromosomal theory of heredity in a matter of years).

Then Koltsov moved to Munich, where the main experiments had to be carried out in an apartment he rented. He managed to get a microscope and a microtome, which made it possible to make sections from biological material suitable for examination under a microscope. Koltsov was an excellent draftsman; his finest drawings of paintings observed under a microscope are striking in their accuracy. Even in the middle of the 20th century, when microphotographic technology reached perfection, his drawings competed with microphotographs in the abundance and accuracy of details, in the clarity of reflection of the observed processes.

Based on the results of his first trip, he wrote a large book, “Development of the head of the lamprey. Towards the doctrine of metamerism of the head of vertebrates,” printed in two languages - German and Russian.

SECOND TRIP TO EUROPE AND START OF WORK ON CELL PHYSICAL CHEMISTRYAt the end of 1899, Koltsov returned to Moscow, and in 1900 he began teaching the first cytology course in Russia at Moscow University as a private assistant professor. In 1901 he defended his master's thesis and on January 1, 1902, he again went to work in the West for two years, first to Germany, and then to Naples and Ville-Franche.

Koltsov was 30 years old at that time. His experiments led to a discovery on a global scale - the discovery in 1903 of a “hard cellular skeleton” in seemingly delicate cells. Before him, scientists believed that cells take their shape depending on the osmotic pressure of the contents filling the cell. Koltsov challenged this fundamental conclusion and derived a new principle, according to which, the more powerful and branched the various structures of the framework that holds the shape of cells, the more this shape deviates from the spherical one. He proposed the term “cytoskeleton”, studied intracellular cords in many types of cells, investigated their branching, and used chemical methods to identify conditions for the stability of the cytoskeleton.

It was only in the late 1970s that scientists began to systematically study microtubules and other intracellular cords that the term “cytoskeleton” was proposed anew, and only in the last third of the 20th century did cell structure specialists begin to recognize its universal significance. This means that Koltsov was at least three quarters of a century ahead of the progress of science! All biologists of our time are convinced that the concept of the cytoskeleton emerged quite recently. But from the beginning of the 20th century, for three decades, the classic of biology Richard Goldschmidt did not stop explaining in his books translated into many languages the “Koltsov cytoskeleton principle” and the dependence of the three-dimensional structure of cells on the position and state of intracellular “elastic fibers” discovered by the Russian scientist. Recalling the time spent with Koltsov, Goldschmidt - a witness to the birth of this principle - wrote in his declining years: "...there was the brilliant Nikolai Koltsov, perhaps the best Russian zoologist, a benevolent, incomprehensibly educated, clear-thinking scientist, adored by everyone who knew him." knew."

"KOLTSOVSKY PRINCIPLES"Returning to Russia at the end of 1903, Koltsov resumed lecturing at Moscow University and actively continued research into the physical chemistry of cells. In December 1905, a revolution began in Russia, and in January 1906 he had to defend his doctoral dissertation. The experiments were completed long ago, the dissertation was written, and the defense date was announced. By receiving his doctorate, Koltsov ensured his unconditional promotion to extraordinary professor—all researchers dreamed of such a fate. However, external events changed the course of academic affairs. By the decision of the government, the university was actually occupied by troops, lectures and laboratory classes were canceled, and students were forbidden to even enter the university territory. As Koltsov later recalled, the defense was appointed literally “a few days after the bloody suppression of the December revolution.”

“I refused to defend my dissertation on such days behind closed doors - the students were on strike - and decided that I did not need a doctorate,” he wrote. “Later, with my speeches during the revolutionary months, I completely upset relations with the official professorship, and the thought of defending my dissertation never crossed my mind."

It should be noted that students of the Moscow Imperial University were almost the instigators of the riots in Moscow. It is interesting that one of the leaders of the student body during the revolution of 1905 was Koltsov’s distant relative Sergei Chetverikov, who at that time was studying at the university and was elected to the Central Student Council, and from him (the only one directly from the Russian student body) delegated to the All-Russian Strike Committee. (In 1955, Sergei Sergeevich Chetverikov dictated to me his memories of that time, published much later).

In 1906, Koltsov published a brochure “In Memory of the Fallen”, the purpose of which is perfectly revealed by the explanation printed on the cover: “In memory of the fallen. Victims from among Moscow students in October and December days. Income from the publication goes to the committee for providing assistance to prisoners and amnestied persons. Price 50 cop. Moscow. 1906".

The brochure describes the circumstances of the death, gives the names of the victims, excerpts from newspapers, Black Hundred calls emanating from government circles, and even the speech of the tsar himself, in which he thanked the student killers for the fact that “sedition in Moscow was broken,” many are named of murderers. The pamphlet was directly directed against the Black Hundred thinking and actions of the Russian government, so it is no wonder that it was ordered to be confiscated.

The incident was brought to the attention of the director of the Institute of Comparative Anatomy, M. A. Menzbir. Koltsov was required to vacate the office he occupied as of September 1, 1906, and was prohibited from managing the library. “Restrained and reserved,” as those close to him characterized him, Koltsov wrote a frank (and, if you look at it from the other side, defiant) letter to Menzbier, calling on him to accept his point of view on public life and generally focus on assessing his scientific work, since they are scientists:

“I would like, dear Mikhail Alexandrovich, that you, before reacting one way or another to this letter, remember that there was a time when you treated my scientific works with a certain respect, saw me as your student. After all, no matter how things turned out our social and political convictions, I think, after all, the most valuable thing in your life and in my life is our relationship to science, and the most that we are able to produce is to work scientifically with our own hands and the hands of our students.”

The answer was an unconditional ban on work in the institute's laboratory. Disagreements with Menzbier reached the extreme limit. Nikolai Konstantinovich asked to leave him at least one room at the institute - completely empty and was going to buy a microscope and other instruments with his meager funds. This was categorically denied to him. Then he decided to appeal to the university’s senior management with a similar request. The refusal followed immediately. Menzbier at this time was already listed not only as the director of the institute, the head of the department, but also as an assistant to the rector and a member of the university presidium. Koltsov, in a conversation with the rector, heard that all the refusals were connected not simply with his unreliability, but with the fact that one of the university professors, who had known him well for many years, testified against him and reported unfavorable information about him. It was not difficult to guess who this professor was. True, with all the harshness of the order in those tsarist times, hated by democrats, Koltsov was not exiled to Siberia and he could even give lectures, but they paid little money for them: he was not a full-time associate professor, but a private assistant professor, that is, he received only an hourly wage . For his “bad behavior” he was not given funds for his next trip to the Naples station, although other employees under similar circumstances received financial support without difficulty. Koltsov demanded that an official open trial be held, at which the judiciary would indicate the article of the law making scientific activity impossible for him. Of course, no one was going to conduct such a trial. A year later, the university management excommunicated the privatdozent, whose name became too well known as the patron of rebels, not only from the laboratory, but also from teaching.

However, it was not in Koltsov’s character to sprinkle ashes on his head and go ask for forgiveness for his beliefs. He began to look for a new place of work. Back in 1903, he began teaching the course “Cell Organization” in a new educational institution created in Moscow - at the Higher Women's Courses of Professor V.I. Guerrier, which existed on private donations and on funds contributed by students for training. The students highly appreciated the brilliant lecturer Koltsov. Then a well-known figure in the field of charity, gold miner A.L. Shanyavsky, collected donations from rich people, contributed the lion's share himself, and the Moscow City People's University was opened in Moscow, which was more often called Shanyavsky's Private University. On April 28, 1909, Koltsov moved to this university, where he created a laboratory, and immediately his former students flocked to him from the Imperial University.

And in 1911 he lent a helping hand to Menzbier. That year, on February 1, Lev Aristideovich Kasso, a lawyer by training, took office as Minister of Public Education (by the way, during his student years he studied mainly in the freedom-loving West - in France and Germany and since 1899 he served as a professor at Moscow University). On his first day as minister, he issued a draconian decree that abolished almost all university freedoms and turned universities into a kind of barracks. The rector of Moscow University A. A. Manuilov, the vice-rector and the assistant to the rector resigned in protest against these police innovations. Casso accepted his resignation on the day the applications were submitted - February 2, 1911. In response, about four hundred university professors and staff followed the example of the rector and vice-rector in February and also resigned. And no matter how law-abiding Menzbir was, he was in his own way a man of convictions. He also resigned. Then he was invited to work at the Higher Women’s Courses of the Rings. Menzbier was indescribably touched; the old relationship could have been restored, but the student who had done a good deed remained withdrawn and cold; he was never seen to be good-natured. After the Bolsheviks came to power in November 1917, both Koltsov and Menzbier returned to Moscow University, but headed different departments.

Firmness of convictions, high morality, love of freedom and a sense of expediency created Koltsov’s strongest reputation. His name has taken root in world science; the principle of the cytoskeleton has been included in German, English, Italian, American, Spanish and Russian textbooks. In 1911, an expanded edition of Koltsov’s book on the cytoskeleton was published in German. In a large monograph, R. Goldschmidt transferred the principle of Koltsov’s cytoskeleton to explain the shape of muscle and nerve cells. Scientists from the University of Heidelberg reported that they have successfully applied the Koltsev principle to the study of single-celled organisms. The Scottish scientist Darcy W. Thompson (who later became president of the Scottish Academy of Sciences) in his monograph “On Form and Growth” explained in detail Koltsov’s principle and reported how this principle helped him in his research. Max Hartmann, already recognized as a leader in biology, in his book “General Biology,” which became a classic and was reprinted many times, based the first two chapters of the first volume on a description of Koltsov’s principle. In the USA, the great Edmund Wilson publicly spoke about the principle of the cytoskeleton and about other works of Koltsov, referred to the work of his students, and in general, put Koltsov in first place among biologists of his generation.

Therefore, it was not surprising that in 1915 the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences invited Koltsov to move to the northern capital, where they were going to create a new huge biological laboratory for him and elect him an academician accordingly. Koltsov showed his integrity here too: he refused to leave Moscow and had to be content with the title of corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences.

CREATION OF THE INSTITUTE OF EXPERIMENTAL BIOLOGYIn 1916, Koltsov was involved in the creation, with the money of patrons (Kh. S. Ledentsov, A. L. Shanyavsky, book publisher A. F. Marx and others), of a number of research institutes independent of the state. Thus, in the summer of 1917, a few months before the Bolsheviks carried out a coup d’etat, the Institute of Experimental Biology (IEB) was opened in Moscow, headed by Koltsov.

When considering the principles of creating the institute, Nikolai Konstantinovich proceeded from the idea that each of the few employees should be a unique specialist. Each corresponded to the level of modern science, each laboratory sought to become a center for the crystallization of pioneering ideas. To conduct research in natural conditions, a small experimental station was used near Moscow, in Zvenigorod. Later, in 1919, a station on the genetics of farm animals was created near the village of Anikovo. The institute was initially located in just a few rooms in a building on Sivtsev Vrazhek and only in 1925 received a beautiful, but by no means impressively large, building in the small street Vorontsovo Pole (later Obukha Street) in the old part of Moscow (now the Indian Embassy is located in this mansion).

KOLTSOV AMONG THE CONSPIRACY AGAINST THE BOLSHEVIKSThe very first actions of the Soviet government alienated the best people of Russia, who, risking their fortune, name and even their very existence, fought against the gendarmerie attitude towards the human person. The slogans of the Bolsheviks turned out to be demagogic toys. The Bolsheviks found themselves needing neither social revolutionaries (SRs), nor social democrats (SD), nor constitutional democrats (cadets), nor other democratically minded people; moreover, the Bolsheviks, who were striving for monopolism, began to persecute them. The press organs of the democrats were immediately banned, and the activity of the security officers was directed against the democrats themselves. In the very first days after the revolution, G.V. Plekhanov’s apartment was searched, and he himself, the recognized leader of free thought in Russia (by the way, Lenin’s teacher), was placed under house arrest. Many prominent representatives of other democratic organizations were arrested, killed, and expelled from the country. Dissent (in other words, democratic choice) turned out to be a state crime.

Is it any wonder that those people who only recently were called advanced were now considered by the Bolsheviks as enemies of the new order. Naturally, supporters of democracy began to seriously think about how to free the country from the dominance of the insane Robespierres and bloodthirsty Maratians. The Jacobin habits of the Bolsheviks frightened the entire society. Groups arose in the country that united people who were looking for ways to liberate Russia from the power of the Bolsheviks, groups that were going to fight them in feasible and legal ways.

In one of these groups, Koltsov found himself in a leading role (not a former count, not a millionaire who had lost his wealth, not an embittered person). Disappointed in the implementation of the ideals of the revolution, Koltsov and his friends created an underground organization (some believe that it was composed of cadets). We know too little today to say anything definite about its activities, but the fact remains: the “National Center” - as the security officers called this organization in their reports - was discovered in 1920. Koltsov played the most sensitive role in it: he was responsible for the financial side of the work, he was the treasurer (which means his friends in the organization trusted him!). In 1920, all the identified conspirators - 28 people, including Koltsov - were arrested by the security officers. The fact that Koltsov’s friends gathered at his apartment was also blamed on the professor.

Koltsov was sentenced to death. Despite this sentence, Koltsov was not demoralized and in prison behaved like a real researcher. In the cell, he began to record the state of various functions of the body, carefully recording all indicators. He later published a serious study on changes in these functions in a person sentenced to death in the first issue of Izvestia of the Institute of Experimental Biology (1921). Fortunately, a close friend, Maxim Gorky, stood up for Koltsov, turning directly to Lenin. Thanks to his intercession, Koltsov was sentenced in 1920 to only five years in prison and was released after some time. And since the release was granted by Lenin himself, Koltsov was no longer publicly persecuted for these actions in Soviet times and his anti-Bolshevik activities were not even remembered. Perhaps Koltsov’s open position as an enemy of Bolshevism, which the security officers could never forget, saved him from the ax that hung over other people suspected of disloyalty to the regime and arrested a second time in the 20s and 30s. The authorities also knew that Koltsov never gave in to mental weakness and did not stoop to compromise in matters of morality.

An important role in such an indestructible strength of Koltsov’s character and inconsistency with the line of decency and honesty was played in his life by his wife, who was equally strong in spirit and morals - Maria Polievktovna Sadovnikova-Koltsova (nee Shorygina, her brother Pavel Polievktovich Shorygin - a major organic chemist, academician of the USSR Academy of Sciences , discoverer of the metallization reaction of hydrocarbons). She was Koltsov's student at Shanyavsky University, then an assistant in his laboratory. They fell in love with each other for the rest of their lives selflessly and passionately. They lived not just in perfect harmony, but inextricably: all affairs were common (Maria Polievktovna became a famous zoopsychologist and conducted experiments at the Kolkovo Institute), and outside of common affairs, everyone had nothing - neither in thoughts nor in reality. The couple occupied an apartment on the second floor of the institute, next to it was Koltsov’s office. Many years later, Boris Lvovich Astaurov and Pyotr Fomich Rokitsky, who became academicians, recalled:

“When any of the artists or singers came to the Koltsov family (and the Koltsovs were friends with many - V.I. Kachalov, N.A. Obukhova, the sculptor V.I. Mukhina, whose husband worked for Koltsov, with A.V. Lunacharsky, A. M. Gorky and others. - V.S.), he often asked to perform something for his employees. And then a signal was transmitted: quickly go into the hall, Obukhova (Dzerzhinskaya or Dolivo-Sobotnitsky) will sing or the Beethoven trio will play. It was here, in a small hall of the institute, that we first saw and heard wonderful artists."

In those years, theoretical biological institutes were not created in the country (the government was stingy with money for this). Therefore, Koltsov sought to help the work of small but highly effective scientific stations outside Moscow. The Zvenigorod hydrophysiological station, built under the patronage of Koltsov by his student Skadovsky, and the Anikovskaya genetic station, founded by Koltsov himself, have already been mentioned. He also established laboratories at the genetic department of the Commission for the Study of Productive Forces (KEPS) of the Academy of Sciences, at the All-Union Institute of Animal Husbandry, a biological station in Bakuriani in Georgia, he also helped the development of the Kropotovsky biological station, then his students, with his participation, created new research centers in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Georgia. Koltsov did not like gigantomania and preferred to create small laboratories (unlike, for example, N.I. Vavilov, who, promising the government to develop new crops for agriculture, managed in the 1930s to receive huge funds from the state budget and increase the number of employees of the All-Union Institute crop production up to 1700 people). At the Institute of Experimental Biology itself, Koltsov managed to collect the best library of scientific literature in the country. He was the first to read all the magazines, and then the employees looked through the notes made in the margins of the magazines by the boss, who marked who exactly should read this or that article. Even when people left his institute for various reasons, Koltsov continued to mark articles and pages of books that were important for their professional growth, and scientists who came to the institute on business were suddenly surprised to discover that their name still appeared in the margins of the pages of new publications : Koltsov never erased anyone from his memory and never held or accumulated any grudge against those who left.

“Koltsov was aware of the smallest details of each work,” recall B. L. Astaurov and P. F. Rokitsky. “The employees were accustomed to hearing the quick steps of a man already gray-haired like a harrier, but with youthful vivacity running up the stairs, making his rigorous daily rounds laboratories to get acquainted with the progress of work, to talk with each employee. The lucky one who made some interesting discovery became at the same time a martyr, since he did not have time to answer the persistent question twice a day: “Well, what’s new with you? ".

The Institute of Experimental Biology has acquired a high reputation in the world. Important foreign guests frequented it. Among them, two of Morgan’s students should be noted - K. Bridges and G. Möller (awarded the Nobel Prize in 1946), to whom the head of the department at Columbia University, Edmund Wilson, who created Morgan’s laboratory and was considered the latter’s formal superior, probably told a lot about Koltsov. Möller, filled with theoretical (correspondence) love for socialist ideas, having arrived in Russia for the first time in 1922, not only visited the IEB, but also brought with him a small collection of Drosophila mutants (about 20 mutant lines). The largest biochemist of microorganisms came, born in Ukraine, who graduated from a gymnasium in Odessa as an external student in 1910 and emigrated to the USA in the same year, Zelmon Abraham (Zalman Abramovich) Waksman, who received the Nobel Prize in 1952 for the discovery of streptomycin. Guests from England were the founder of genetics, who proposed the term “genetics” itself, William Batson, and the largest geneticist and evolutionist Syria Darlington, as well as John Haldane, a scientist who changed his specialization several times (from genetics to biochemistry and biostatistics), a convinced communist. Outstanding German scientists Erwin Baur, revered as the patriarch of German biology, Oscar Vogt (later the organizer of the Brain Institute in the USSR and the Institute for the Study of Brain Processes in Berlin, where N.V. Timofeev-Resovsky worked from 1925 to 1945) and the classic of biology Richard Goldschmidt (at the end of his life he moved to work in California, USA) is not the last on the list of IEB guests. In January 1930, Goldschmidt spoke about the Koltsov Institute: “I am amazed and still cannot understand my impressions. I saw such a huge number of young people interested in genetics, which we cannot imagine in Germany. And many of these young geneticists are as versed in the most complex scientific issues as only a few fully established specialists in our country.”

KOLTSOV’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF GENETICS AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGYOn January 1, 1920, the IEB was transferred to the system of the People's Commissariat of Health of the RSFSR. It included laboratories of genetics, cytology, physical and chemical biology, endocrinology, hydrobiology, developmental mechanics, and zoopsychology. The laboratories were headed by people, each of whom, without exception, became an outstanding scientist. The IEB developed methods for culture of tissues and isolated organs, as well as transplantation of organs and tumors (including malignant ones). From an isolated eye rudiment, D. P. Filatov learned to grow the lens and differentiated tissues of the eye. S. N. Skadovsky carried out remarkable, truly pioneering experiments to study the influence of hydrogen ions on aquatic organisms. In general, Koltsov attached special importance to the problem of ion research (outpacing his contemporary science in this matter by half a century) and loved to jokingly, but at the same time quite seriously, repeat that “ion scientists must understand gene scientists, and vice versa!” The first studies of the influence of calcium, sodium, potassium ions on the relaxation and compression of biological structures, as well as their role in the excitation of effector chains, were carried out by Koltsov himself at the beginning of the century. He wrote: “The work of an excited nerve at its effector end is reduced primarily to an increase in the concentration of Ca relative to Na,” thereby anticipating important scientific directions of today.

The Institute of Experimental Biology quickly became a center in the country for the study of cells, their structure, physicochemical properties, and later genetics. Outstanding successes in the latter direction were due to the fact that Sergei Sergeevich Chetverikov created his famous laboratory at the Koltsov Institute, who in 1926 laid the foundations of a new direction of science - population genetics, and his students - N.V. Timofeev-Resovsky, B.L. Astaurov, P.F. Rokitsky, D.D. Romashov, S.M. Gershenzon and others received the first experimental evidence of the correctness of their teacher’s views. (In 1928, S.S. Chetverikov, due to a dirty political slander, was arrested and in 1929 exiled to the Urals. The rapid development of population genetics in the USSR, which began under Chetverikov, after that noticeably weakened, and soon English and American scientists caught up with the Russians, realizing the importance problems identified and developed by Chetverikov).

In 1927, Koltsov came up with a hypothesis in which he argued that hereditary properties should be written in special giant molecules, each gene should be represented by a segment of this giant molecule, and the molecules themselves should consist of two identical threads (one double molecule per chromosome). According to Koltsov, each single thread during division will pass into a daughter cell, and its mirror copy will be synthesized on it (the information recorded in the thread will be reproduced in the mirror copy). In other words, he formulated the matrix principle of reproducing hereditary molecules (as Koltsov called it, “from a molecule - a molecule”). The creation of new identical double hereditary molecules would ensure the preservation of continuity in hereditary records, he believed. All four assumptions were anticipations of the future progress of science. It was only in 1953 that J. Watson and F. Crick proposed a theoretical model of the DNA double helix and received the Nobel Prize for this in 1962 (they, as Watson told me in 1988, had not even heard of Koltsov’s idea), and later it was established that that in fact there is one double-stranded DNA molecule per chromosome.

KOLTSOV - PUBLIC FIGUREKoltsov’s contribution to the development of Russian biology and Russian science as a whole would be incompletely outlined if his humanitarian activities remained in the shadows. He did a lot not only for women's education in Russia. He more than once stood up for the honor and dignity of many Russian scientists who were unfairly offended, slandered, or arrested. And in Soviet times, he did not change his principles. (Sergei Sergeevich Chetverikov told me at the end of his days that Koltsov, immediately after the spread of false rumors about Chetverikov’s appeal to the newspapers with an apolitical statement, without fear of anything, dropped all his affairs and went to defend him in various instances, which, apparently, greatly helped Chetverikov: there was no trial as such at all, it was replaced by administrative exile, and Chetverikov’s exile was also unusual - his friends saw him off at the station with champagne and flowers. However, in Sverdlovsk itself, where Chetverikov was serving his exile, he had a hard time.)

Koltsov wrote vividly and a lot. He did not confine himself within the framework of purely scientific creativity, he had a style that captivates readers, although he never stooped to beauty, deliberate entertaining and simplification. To this day, the journal Nature plays an important contribution to the dissemination of scientific knowledge. Its publication was initiated in 1912 by zoologist and psychologist V. A. Wagner and chemist L. V. Pisarzhevsky, who invited Nikolai Konstantinovich to become editor-in-chief of Priroda (he remained until 1930). It was thanks to Koltsov’s efforts that Vernadsky, Mechnikov, Pavlov, Chichibabin, Lazarev, Metalnikov, Komarov, Tarasevich, Kulagin and other outstanding Russian scientists became the authors of “Nature”. He also founded, as a supplement to “Nature,” the series “Classics of Natural Science,” in which books appeared dedicated to the lives of Pavlov, Mechnikov, Sechenov and many other scientists. Since 1916, he edited the "Proceedings of the Biological Laboratory", published in the series "Scientific Notes of the Moscow City People's University named after A.L. Shanyavsky", then organized the journals "News of Experimental Biology" (1921), "Advances in Experimental Biology" (began publishing in 1922), "Biological Journal" and a number of other publications. He also took part in the publication of magazines and almanacs “Scientific Word”, “Our Achievements”, “Socialist Reconstruction and Science”. He was editor of the biological department of the Great Medical Encyclopedia and co-editor of the biological department of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, and wrote many popular science brochures.

There was another side of Nikolai Konstantinovich’s interests that was used to attack him. At the beginning of the century, Koltsov became acquainted with the first works on the inheritance of mental abilities in humans, planned to organize a department of human genetics at his institute and began to collect literature and information on this problem. At that time, following the Briton Francis Galton, Darwin's nephew, biologists became interested in changes in human heredity and began to study human genetics, calling this direction eugenics. In 1920, Koltsov was elected chairman of the Russian Eugenics Society and remained so until the cessation of the Society’s work in 1929. Since 1922, he has been the editor (since 1924 - co-editor) of the Russian Eugenics Journal, in which he published his speech “Improving the Human Race,” delivered on October 20, 1921 at the annual meeting of the Russian Eugenics Society. In this magazine in 1926 his study “Genealogies of our nominees” appeared.

POLITICAN ATTACKS ON KOLTSOVKoltsov’s independent position not only in science, but also in social activities irritated the authorities. The first to launch malicious attacks on Koltsov were figures from the Society of Marxist Biologists in March 1931. Koltsov began to be subjected to harsh public attacks in the spring of 1937. An example was set by the head of the agricultural department of the Central Committee of the party, Ya. A. Yakovlev, who qualified Koltsov as “a fascist obscurantist... trying to turn genetics into a weapon of reactionary political struggle.”

One of the reasons for this attitude towards Koltsov was that during a discussion on genetics and selection in December 1936, Nikolai Konstantinovich behaved irreconcilably towards those who attacked genetics (primarily Lysenko’s supporters). Understanding, perhaps better and more clearly than all his colleagues, what the organizers of the discussion were driving towards, after the session closed, in January 1937 he sent a letter to the President of the All-Russian Academy of Agricultural Sciences (copies to Yakovlev and the head of the science department of the Central Committee K. Ya. Bauman) in which directly and honestly stated that organizing SUCH a discussion is patronizing liars and demagogues and will not bring any benefit to either science or the country. He focused on the unacceptable situation with the teaching of genetics in universities, especially in agronomy and livestock.

“The teachers of genetics at provincial universities turned out to be especially unhappy... They will return to their departments, and the students will tell them that they do not want to listen to tendentious anti-Darwinian genetics. After all, they only know this characteristic of genetics from newspapers that printed biased and often completely illiterate reports about the sessions of the session. What is the value, for example, of the report in Pravda on December 27... What would you call such a “truth”? Will it really remain unrefuted?

We need to correct the mistakes made. After all, perhaps more than one graduating class of agronomists will suffer from the resulting destruction of genetics as a result of the session... What would you say if chemistry teaching was abolished in agricultural universities? And genetics, this wonderful achievement of the human mind, approaching chemistry in its accuracy, is no less necessary for the education of an agronomist.

It is impossible to replace genetics with Darwinism, just as it is impossible to replace differential calculus with algebra (of course, and vice versa). Half a century is a long period in science, and the Soviet Union cannot lag behind by 50 years in even one area.

Something needs to be done and we cannot delay... History will first of all ask us why we did not protest against the attack on science that was unworthy of the Soviet Union... Ignorance in the next issues of agronomists will cost the country millions of tons of bread. But we love our country no less than the party Bolsheviks and are proud of the successes of social construction. That’s why I don’t want and can’t remain silent, although I know that as a result of my speech, a feuilleton may appear in some newspaper, throwing mud at me.”

He showed this letter to many participants in the session, including N.I. Vavilov, urging them to join his assessment. The majority, including Vavilov, joined in words, but only in words, preferring to remain silent in public, because the author, among other things, attacked the main mouthpiece of the party, the newspaper Pravda, claiming that there was no truth in its reports on the session. The letter was discussed at a meeting of the Presidium of VASKhNIL on January 16, 1937. Vice-President of VASKHNIL Vavilov refused to support Koltsov.

Koltsov’s openly negative attitude towards politicking and belittling genetics gave rise to no less open attacks against him. Particularly harsh accusations were made on March 26-29 and April 1, 1937 at meetings of the active members of the Presidium of the All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences. The pretext for the urgent collection of assets was the arrest of a number of employees of the Presidium and several heads of institutes of this academy (Anton Kuzmich Zaporozhets - director of the All-Union Institute of Fertilizers and Agricultural Soil Science, Vladimir Vladimirovich Stanchinsky - director of the Institute of Agricultural Hybridization and Animal Acclimatization "Askania-Nova" and others).

The first accusations against Koltsov were made by the president of the academy, A. I. Muralov, at the very beginning of the meeting. Speaking about ideological omissions, he stated: “... on this front we have not made all the conclusions that are mandatory for workers in agricultural science, conclusions arising from the fact of the capitalist encirclement of the USSR and the need to maximize vigilance. A striking example of this is the letter of Academician Koltsov, sent to the president of the academy after the discussion, saying that the discussion had brought no benefit or only harm."

Koltsov was not afraid and, having listened to the repeated accusations against him, asked to speak and without hesitation rejected the unfair attacks: “The newspapers incorrectly informed about the essence of the discussion that was taking place. From them it is impossible to get a clear idea of what was said. As a result, the situation of geneticists is very difficult. It has become difficult to teach genetics."

Such an accusation of the Soviet press - of distorting the truth - was an extraordinary event in those years: the printed word had almost mystical power, so it took enormous courage to speak out as Koltsov allowed himself. In addition, Nikolai Konstantinovich condemned his colleagues who chose to remain silent, and mentioned Vavilov, who said on the sidelines that “2/3 of those present would have signed his letter,” but when it came time to vote, they preferred to vote for the resolution of the authorities, who rejected Koltsov’s views . What he said next can be understood from the report on the asset: “Academician Koltsov believes that he is right, that he does not take back a single word from his letter and that the letter was genuine criticism. “I will not deny that “What I said,” finishes Academician Koltsov.”

After such a statement, the guardians of the purity of party views rushed to attack. They began to remember that Koltsov was one of the founders of the Russian Eugenics Society, forgetting, however, to mention that the society was founded in 1920 and ceased to exist in 1929 at the suggestion of Koltsov. Of course, politicians did not mention that Koltsov had already become a classic of biology during his lifetime, that he created the best biological institute in Russia. Instead, one of the leaders of the academy - its scientific secretary and executive editor of the VASKHNIL Bulletin, academician L. S. Margolin said: “N. K. Koltsov ... zealously defended fascist, racist concepts,” although there was never even a hint of this in his works Koltsov was not there. The line of political accusations was used by the person closest to Lysenko, I. I. Prezent, who openly misinterpreted what Koltsov said, asserting: “Academician Koltsov spoke here to declare that he does not renounce a single word of his fascist nonsense.” He ended the Presentation, as he knew how to do so perfectly, on a high demagogic note: “Soviet science is not a territorial, not geographical concept, it is a social-class concept. Our academy should think about the social-class line of science, then we will have a real Bolshevik academy , not making the mistakes that she now has."

The speech of the director of the All-Union Institute of Animal Husbandry G.E. Ermakov was nothing more than incitement to the arrest of Koltsov:

“But when Academician Koltsov comes to the podium and defends his fascist nonsense, is there really a place for “tolerance” here, aren’t we obliged to say that this is direct counter-revolution.”

Thanks to these speeches, the compilers of the report on the past party activity had the opportunity to write the following lines:

“The indignation of the activists at the speeches of Academician Koltsov, who tried to defend the reactionary, fascist principles set out in his notorious pamphlet, was fully reflected in the subsequent speeches of the meeting participants and in the resolution adopted by the activists.”

The report also included lines from the resolution:

“The meeting considers it completely unacceptable that Academician Koltsov, at a meeting of activists, came out with a defense of his eugenic teachings of a clearly fascist order, and demands from Academician N.K. Koltsov a completely definite assessment of his harmful teachings.”

However, it was not possible to intimidate Koltsov. At the end of the meeting, he took the floor again and concluded his speech with the following phrases:

"...I do not renounce what I said and wrote, and I will not renounce, and you will not intimidate me with any threats. You can deprive me of the title of academician, but I am not afraid, I am not one of the timid. I conclude with the words of Alexei Tolstoy, who wrote them on an occasion very close to this case - in response to the censor who was trying to ban the publication of Darwin's book:

Give up, comrade, intimidation,

Science is not timid.

You can't stop her flow

No traffic jam!"

Vavilov, who was one of the last to speak at the rally, did not support Koltsov with a single word, and even somehow isolated himself from him with pathetic phrases about the need to be vigilant, since the enemies of socialism were operating in the country, his speech did not differ one iota from the speeches of Muralov or Margolin. Perhaps Vavilov did not find the strength to support Koltsov, being offended by him for the criticism voiced at the session of the All-Russian Academy of Agricultural Sciences in October 1936, when Koltsov addressed both the Lysenkoists and their opponents with a call to delve more seriously into the issues under study and did not spare Vavilov himself: “I turn to Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov, do you know genetics properly? No, you don’t... You read our “Biological Journal”, of course, poorly. You haven’t studied Drosophila much, and if you are given a regular student test task, determine that point chromosomes, where a certain mutation lies, then you probably won’t solve this problem right away, since you never took a student course in genetics.”

Another week and a half passed, and Pravda published an article by Yakovlev, in which the party leader in harsh terms characterized genetics as a fascist science and stated that geneticists “for their political purposes” allegedly “carry out a fascist application of the “laws” of this science.” He called Koltsov “an obscurantist and an ignoramus.”

On the same day that Yakovlev’s article was published in Pravda, the newspaper Socialist Agriculture published an article by Prezent and Nurinov, which repeated attacks on genetics and provided a link to Yakovlev’s article (which means that Prezent and Nurinov received the text in advance this article and the guidelines and conspired on how to proceed). The tone of their article was simply ominous:

“In the era of the Stalin Constitution, in the age of genuine democracy of the working people... we are obliged to demand from scientists a clear and unambiguous answer, with whom are they going, what ideology guides them?.. None of our scientists has the right to forget that saboteurs and saboteurs ", the Trotskyist agents of international fascism will try to exploit every crevice, every manifestation of our carelessness in any field, including, not least in the field of science."

Lysenko's Landsknechts allowed themselves the following expressions: “Once upon a time in biblical times, Valaam’s donkey spoke in human language, but in our days the Koltsovo prophetess showed that it is possible to do the other way around.”

In July 1937, in the journal “Socialist Reconstruction of Agriculture,” G. Ermakov and K. Krasnov once again called Koltsov an accomplice of the fascists. Moreover, if earlier he was accused of sympathizing with fascist perversions, now this too has been inverted and the authors of the article informed readers that Koltsov’s views “are no different from the core part of the fascist program! And a fair question arises whether these “scientific” are not the basis of the fascist program works of Academician Koltsov.

The conclusion drawn in the article was definite:

“Koltsov falsifies the history of the labor movement for his own reactionary purposes... Soviet science is not on the path with Koltsov’s “teachings”... The fight against formal genetics, led by Koltsov, the consistent struggle for Darwinian genetics (isn’t it a wonderful turn of phrase - “Darwinian genetics” ", especially if we remember that in Darwin’s time genetics did not yet exist! - V.S.) is an indispensable condition for the magnificent flowering of our biological science."

Removal of N.K. Koltsov from the post of director of the Institute of Experimental BiologyIn 1938, after the USSR Academy of Sciences was accused at a meeting of the Soviet government of the unsatisfactory development of scientific and applied work in the USSR, an order from above announced the election of a large number of new members of the academy. In theory, academic scientists should have elected the best scientists to the USSR Academy of Sciences, but in practice, politicians who clearly understood the aspirations of the leaders sought to do everything possible to elect obedient people as academicians and corresponding members, to make the academy tame. In January 1939, in Pravda, academicians A. N. Bakh and B. A. Keller, close to the top, and six young scientists who joined them - employees of the Vavilov Institute of Genetics of the USSR Academy of Sciences - made a statement that Koltsov and L. S. Berg - an outstanding zoogeographer, evolutionist and traveler - cannot be elected to the academic staff. Their letter was entitled: “There is no place for false scientists in the Academy of Sciences.” It’s hard to believe that Vavilov’s employees signed this libel, but the fact remains.

After such an article, neither Koltsov nor Berg became academicians (the latter was elected academician in 1946), and the Presidium of the USSR Academy of Sciences appointed a special commission to examine cases at the Koltsov Institute. Members of the commission began visiting the institute and talking with employees. Lysenko came to Vorontsovo Pole several times. In the end, what seemed to be the necessary materials condemning Koltsov were collected, and a general meeting of the institute’s staff was scheduled, at which the commission was going to listen to the employees and read out its decision.